Len's Blog #3: Philip Glass

Minimalism; an extraordinary film score; and a director who loves to post.

I recently read The Rest is Noise, a riveting—if you're into this sort of thing—history of classical music in the 20th century written by Alex Ross, music critic for The New Yorker. It covers composers and music from across the globe during the political and cultural upheaval of the last century, from Stravinsky's Rite of Spring to the state sanctioned composers in the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, from the atonal music of continental Europe to the beginnings of American jazz. The post-WWII section discusses American avant-garde and minimalism, schools of music that I was totally unfamiliar with.

The chapter on minimalism briefly describes the career of Philip Glass (born 1937). Unlike the rest of the postmodern composers mentioned in the book, I had already heard of Philip Glass, because he wrote the music for Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), which is probably my favorite film score.1 Similarly to Steve Reich, the other notable New York City-based minimalist composer,2 many of Glass's compositions revolve around simple melodic patterns that repeat at high speed, ad nauseam. At the same time, these composers play with rhythm and make minute additions or subtractions to the buzzing patterns to create slower, surprising tectonic shifts—Ross describes these turns as creating a transcendent "a-ha" effect for the listener. He cites a critic who compares this method to the imperceptibly quick shuttering of nearly identical photographs that creates the much slower, illusory moving picture of film.

I first heard part of Glass's frenetic, tragic score for Mishima on the soundtrack to HBO's The Leftovers when it aired in 2014. The segment of Glass’s score used in the show was performed by strings, and I assumed that the entire composition was originally written only for strings. But when I listened to the original recording of the full 1985 score, I was surprised to hear bells, synths, a military snare drum, a harp, sometimes a full orchestra. The changes in instrumentation create different moods, but each movement shares the same desperate, barely-contained driving force.

Throughout the Mishima score, Glass uses a repeated two-note pattern (one-two, one-two), then overlays a fluctuating burst of triplets (one-two-three, one-two-three). It’s the most basic example of polyrhythm, but that simple syncopation resonates with me in almost any musical context. Taken as a whole, Glass’s score is modular, repetitive, and achingly emotional, giving a sometimes overpowering sense of doomed obsession. The ascending and descending triplets feel like they are urgently building to something, climbing higher, then the momentum stalls out and subsides in repeating patterns of decreasing length, like an overworked machine that short-circuits, or like someone controlling their breath in preparation for some Olympic feat, who instead gets stuck hyperventilating—grand ambitions devolve into a panic attack.

One of my favorite moments in the score is when a jazzy electric guitar and swing-style percussion emerge out of nowhere, still playing the spinning triplets that alternate with a one-two-one-two rhythm, but with a swagger this time around. After a few stanzas, the melancholy violin returns over the top of the jazz trio to continue the unstoppable tragic inertia.

Paul Schrader was the odd outsider of the New Hollywood filmmakers who came up during the 70s, and he never became a household name like his peers Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, or George Lucas. Schrader first made it big when he wrote the screenplay for Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976), which set the stage for his subsequent directing career—his filmography is filled with lonely, sexually frustrated men who fixate on achieving glory or liberation through dramatic acts of violence. (You might perceive an early version of the modern “men’s rights activist” in this description.) On one level, Schrader seems to identify with Travis Bickle, the misanthropic protagonist of Taxi Driver played by Robert De Niro. In a 2011 interview, Schrader said “[Taxi Driver] was essentially written as self-therapy. I was in a desperate place and this character was starting to take over my life. I felt I had to write him so I wouldn’t become him."

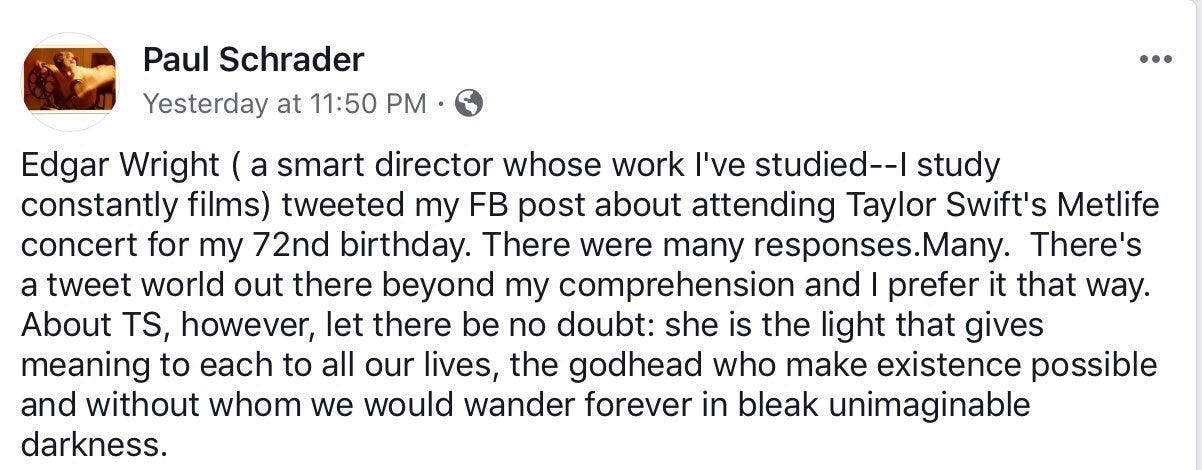

Like his films, Paul Schrader is complex and abrasive. I won’t attempt to pinpoint his personal beliefs, but I’ll mention that a few of his films have insightful progressive politics, and that in interviews (and in the films themselves) he appears to have a healthy enough perspective on his "violent male loner" protagonists. This is only slightly complicated by the fact that he is now in his 70s and addicted to posting on Facebook in rambling, unsolicited pop culture commentary and old-man-yells-at-cloud screeds against PC culture. His posts swing from problematic—often in some new, inventive way—to hilariously absurd, like when he revealed that he is a die-hard Swiftie.

Schrader's filmography is also a strange mix. He’s directed multiple critical (if not box office) hits, and if average ratings on Letterboxd are to be trusted, he’s directed a number of real stinkers. I’ve watched a few of the good ones, but I want to watch more, especially First Reformed, his 2017 drama starring Ethan Hawke that many seem to agree is a late-career triumph.

In 1985, Schrader directed Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, a biopic (in a loose sense) about Yukio Mishima, a controversial Japanese writer/celebrity who wrote beloved novels, poetry, and essays and was considered for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1968. He also professed radical far right beliefs and created a small private army with the dream of reviving the former militaristic government of imperial Japan. Schrader’s film was never officially released in Japan due to the influence of Mishima’s widowed wife and threats from far right Japanese groups, who opposed the film’s depiction of Mishima’s homosexuality.3

The movie follows the narratives of three different works of fiction written by Mishima, tied together by the overarching biographical narrative of his life. The sections are distinguished by color and film style—black and white for the childhood and adolescent flashbacks; nakedly artificial sets and stark color palettes for the three fictional stories (gold and green for The Golden Pavilion, pink and gray for Kyoko’s House, and black, white and red for Runaway Horses); and messy, naturalistic handheld camerawork for the events of November 25, 1975, which function as the “present day” portion of the multilayered plot. As I alluded to before, Philip Glass’s score relies on different instrumentation for each of the narratives—a string quartet, percussive bells and synths, a jazz trio, a full orchestra.

Schrader's interests and obsessions are on full display, and there’s no doubt that his expansive directorial vision is realized, but the success of the film is due in large part to his choice in collaborators—mainly Eiko Ishioka, the Japanese graphic artist who designed the strikingly colorful expressionistic sets for the three fictional narratives, and Philip Glass, who with Schrader’s encouragement composed the score like he was writing a full-blown opera. Like its score, the film is bleak, overwhelming, and totally unique—a singular masterpiece.

It’s my favorite original score, but my favorite use of music in any movie is probably the classical music in Barry Lyndon (directed by Stanley Kubrick) or maybe one of a few brilliant classical music soundtracks used by director Terrence Malick.

Reich was one of my favorite composers who I learned about from The Rest is Noise. I recommend his meditative, hypnotic "Music for 18 Musicians". (Feel free to skip around in each track if you get bored—I think that’s a totally fair way to engage with this type of thing if you’re not in the right mood/environment to enter an hour-long trance.)

According to interviews included on the Criterion release.